On October 30th, 1938, a radio broadcast on the CBS Radio station "The War of…

Parrot Fancier’s Fever–Part 2

In my last post, I told about how my youngest daughter contracted an obscure illness and we learned about a disease called psittacosis –– also known as Parrot Fancier’s fever. In the process, I discovered a little-known but fascinating history of a pandemic in 1930 that led in part to the creation of what is now known as the National Institute of Health, one of the organizations on the cutting edge of research on COVID19.

It happened in 1930 and lasted only last a few short months, but the some of the details will sound familiar to us as we navigate the current health crisis.

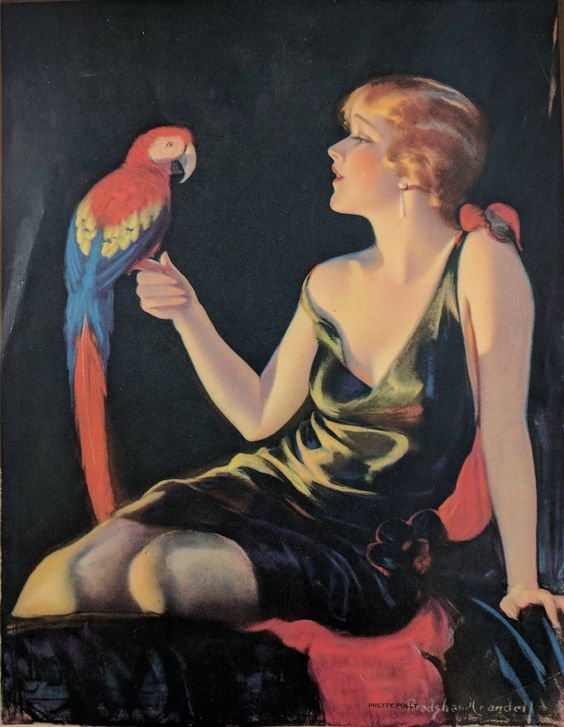

It was the Christmas of 1929, and all the rage to give wealthy young and not-so-young women an exotic parrot for Christmas, usually imported from Argentina. By January of 1930, a mysterious illness began affecting families across the country — usually wealthy families. What’s more, it was the daughters, mothers, and single older women who were falling ill. It started with a high fever and headache, then progressed to pneumonia symptoms.

Doctors almost immediately diagnosed the malady as psittacosis, also known as Parrot fever, Parrot Fancier’s fever, or even Old Maids Pneumonia. It was not an unknown illness worldwide, but rarely seen in the United States. The worst part: there was no known treatment and one in twenty who contracted psittacosis died.

Media panic ensued. (yes, that happened in 1930 as well). Reports, rumors, and theories abounded. Newspapers contradicted each other: “not contagious in man,” announced the New York Times. On the same date, the Washington Post reported the illness “Highly contagious.” Some said eight hundred cases worldwide, some papers reported far less.

Keep in mind these historical facts:

- Newspapers were the only means of getting information to the public

- antibiotics were not yet available

- Americans remember all too well the devastating Influenza outbreak just twelve years earlier that killed fifty million people worldwide, 700,000 of them Americans

By the middle of January, there were fifty reported cases in the United States and seven deaths–but these were not confirmed cases of psittacosis. In fact, later tests revealed several of the deaths had been from other causes. Still, the newspapers continued to report every suspected case and none of the recoveries. Families were told to isolate their feathered pets — some health commissioners even demanded every bird owner to wring their pets’ necks, and a U.S. Navy admiral ordered his sailors to throw their parrots overboard. Many people abandoned their pets on the street rather than have them in their homes.

It was a medical mystery that stoked panic throughout the country — and sold a great number of newspapers.

And as we see in our day, there were opposing opinions. The Bird Dealers, a loose association of importers of exotic birds, claimed the whole thing was a hoax. Parrot fever, they insisted, had never existed in humans and had been a ruse to sell more newspapers. The New Yorker ran a piece that called parrot fever “the latest and most amusing example of the national hypochondria.” One newspaper quoted a Viennese scientist, who believed that Americans were suffering from “mass suggestion.”

In the meantime, scientists were scrambling for information. A team of epidemiologists was put together, led Dr. Charles Armstrong from the Washington D.C. Hygienic Laboratory, a federal office formed in the 1800s. Dr. Armstrong’s team collected diseased birds–both dead and alive–from around the country, blood samples, and lists of people who had purchased parrots for Christmas. Then they went to work to both contain the outbreak and develop a serum for treatment.

On January 13th, the Chicago Daily Tribune reported a landmark success: “parrot fever germ isolated.”

Unfortunately, the team of scientists themselves had been infected with parrot fever. By early February, three of the researchers were dead of the disease and Dr. Armstrong himself was gravely ill with a fever of 104 degrees. George McCoy, the director of the Hygienic Laboratory, took over Armstrong’s work and attempted to save his colleague by injecting him with the blood of a patient who’d recovered from the disease. Armstrong recovered and went on to incinerate every bird, rodent, and rat in the laboratory, seal the facility, and fumigate it with cyanide.

By the end of February, the outbreak was contained–largely due the confiscation and elimination of infected birds.

According to Armstrong’s final report, the Parrot Fever epidemic had infected a total of one hundred and sixty-nine Americans and resulted in thirty-three deaths. He praised the press, without which he said “this outbreak would have largely escaped detection.”

Whether the press actually helped contain the outbreak or incited panic is a matter of opinion. What we do know is that within a few years, antibiotics would become widely used to treat diseases such as psittacosis. In addition, just two months after the panic of parrot fever, on May 26, 1930, the U.S. Congress rewarded Armstrong, McCoy, and the Hygienic Laboratory by expanding its responsibilities and granting it a new name, the National Institute of Health.

Today, the National Institute of Health and its many scientists are working for both contain the spread and find a vaccine against the latest epidemic the human race is facing, COVID19.

Next blog post: The 1623 Malaria outbreak in the Vatican and the treatment discovered by Jesuit priests in South America

This Post Has 2 Comments

Comments are closed.

Fascinating! I love the way you are putting your research skills to work.

I”m not sure why it seems to make me less anxious about COVID19 when I research historical plagues. Seems like it would be the other way around . . .