On October 30th, 1938, a radio broadcast on the CBS Radio station "The War of…

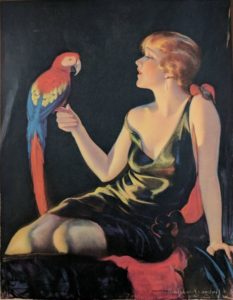

Historic Epidemics: Parrot Fancier Fever Part 1

COVID19 isn’t the first epidemic to hit our world, and it won’t be the last. Since I’m a big believer in learning from history, I’d like to take a look at some of the diseases we’ve faced as a global community in the past couple thousand years and what we’ve learned from them–beginning with an obscure illness I’ve had personal experience with, believe it or not: Parrot Fancier’s Fever.

In 2015, on the last day of a camping trip to North Cascades National Park, my youngest–about twelve at the time–came down with a headache and fever. We didn’t think much of it, kids get sick all the time, right?

Not so this time, as we would soon discover.

But by the time we had packed up the tents and made our way back to my mom’s house two hours away, Anna’s fever had spiked to 103, her headache was unbearable, and she had developed a dry cough. (Sounds familiar, I know, but this was five full years before anyone had heard of COVID19) I took her to the clinic nearby, where the on-call Doc (dressed in a Hawaiian shirt and seemingly more interested in telling me about his recent whitewater rafting trip than observing my daughter’s symptoms) declared her negative for strep and advised ibuprofen and lots of liquids. No antibiotics, no blood tests despite my request for both. Wait it out, he advised.

By the time we flew back to Minnesota a few days later, her fever was down but the headache and cough persisted. Her own pediatrician started doing a series of tests and immediately prescribed an antibiotic. The tests–for everything from Lyme disease to Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever–came back negative and the round of antibiotics didn’t seem to help. I was getting more than a little worried about my normally energetic child’s lethargy.

The next day, I was on the phone with a friend (thank you, Laura!) who wondered in an off-hand manner if Anna might have caught something from her birds. Anna was in 4H and had a few months earlier started keeping a flock of quail in the backyard. “I can’t imagine what,” I remember saying. Nevertheless, when I talked to her stumped doctor later that afternoon, I mentioned that Anna raised quail. The next day, the doctor called back with the strangest diagnosis: “It’s possible your daughter has Parrot Fancier’s fever.”

What? I immediately googled it and found an illness I’d never heard of: Psittacosis.

Psittacosis, characterized by high fever, body aches, severe headache and cough.

That sounded alarmingly familiar.

Transmitted to humans by the airborne inhalation of feather dust, dried feces of infected birds with curved beaks such as parrots, macaws, pigeons.

Curved beaks? I bolted outside to the quail hut and saw that, indeed, those little birds beaks were curved. Back at the clinic, the pediatrician–who was pretty excited to have something other than strep and pink eye to look at, I suspected–took more blood to test for the antibody to this particular bacteria. It came back: Positive. She prescribed her a round of much stronger antibiotics than we’d previously tried. Within days, Anna was back to her energetic self, thank the Lord, and with no lasting effects except a healthy respect for keeping her quail hut clean and watching for sick birds.

Turns out, Parrot Fever–also known as Psittacosis, Parrot Fancier’s Fever, and Old Maid’s Pneumonia–is a real thing. Today, it effects only about ten people in the U.S. each year and is easily treated with antibiotics. But that wasn’t always the case.

P.S. The quail flock was part of our family for many years and supplied us with dozens of tiny eggs each week, until a tragic fire in the hut last year put an end to our bird-raising.

This Post Has 6 Comments

Comments are closed.

This is fascinating! So many things I find I know so little about. With kids in 4H (though not with animals), I’m aware of the caution they use at fair time with swine and avian flus, but this one is new to me.

It was strange and scary. But we didn’t want to make her overly fearful. That’s why we didn’t get rid of the birds. Thanks for reading and stay tuned for the equally strange history of the U.S. epidemic 🙂

Only 10 people a year! Lucky you! I can’t wait to read more.

I know! She’s a magnet. She ended up actually testing positive for Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever also, but the antibodies made it clear she’d had it over a year earlier. Then I had the state and federal health offices calling me to ask questions about both diseases. She’s on some kind of list, I just know it.

The things it doesn’t occur to us to mention to the doctor: “My kid raises quail.” Hmm.

Yeah, I felt like we were on an episode of ‘House’!