Historic Epidemics: The Spanish Flu Didn’t Come From Spain

As we shelter at home and follow the rising numbers of infections and deaths from COVID-19, I have a new understanding and appreciation for the fear and devastation caused by what we know as the Spanish Flu:

-

A worldwide pandemic that spread like wildfire before air travel was even a thing

-

infected over 500 million people (about a third of the population of the planet)

-

over thirty million people died of the virus (a 6% death rate) and 675,000 of the deaths were Americans

-

an alarmly high death rate among children under 5 and for healthy adults between the ages of 15 and 34

There’s much we don’t know about this pandemic and historians and scientists are still looking at it for answers that may help us with our current crisis. But for now, let’s answer a simple question: Did the Spanish Flu come from Spain?

The answer is a definite no.

Theories on the origin of the first outbreak range from the first case reported at Fort Riley, Kansas, to the ground zero occuring in Great Britain, France, or even China.

What do know is the first cases started in the spring of 1918, during the last year of the Great War. This meant soldiers from the United States, Great Britain, most of Europe and Russia were either fighting in trenches, living in camps, or moving between countries on transport ships and crowded trains.

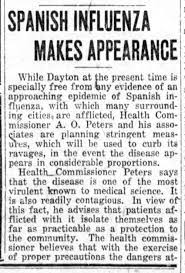

Sadly, the troops fighting on the fronts of Europe and the families at home had no warning of the onslaught of a new disease. The wartime media–for purposes of national security, it was said–was heavily censored and forbidden to report on the virus. The generals didn’t want to dampen the moral of the soldiers or raise a public outcry back home with the war so close to its end.

Spain, on the other hand, was neutral during WWI and the free media there began to report a deadly disease that started with fever and fatigue and progressed rapidly to respiratory distress and death in an alarming percentage of previously healthy people. Coverage increased when the Spanish king, Alfonso XIII came down with the virus and was near death. Americans and other Europeans reading the coverage wrongly assumed that Spain was ground zero and took to calling the illness the Spanish flu or the “Spanish Lady.” The European and American media made no attempt to correct the misnomer.

By the fall of 1918 the war was coming to a close and the second–and much more deadly–wave of the virus hit. Unfortunately, this was also the end of the Great War, and troops carrying the illness were returning to their home countries. In no time at all, the virus reached pandemic proportions. Much like our current crisis with Covid-19, no corner of the globe was spared. Every country reported cases–from Africa to Alaska.

Unfortunately, the myth of the origination in Spain continued, leading some countries to lash out against their Spanish and Mexican citizens. For generations onward, both Spanish and Mexicans were often considered ‘dirty’ and ‘diseased’ because of the outbreak.

There’s much more to understand about the 1918 Influenza, especially now that we’re facing a pandemic of our own. In the next post, we’ll take a look at the treatments recommended for the 1918 Pandemic (including isolation and masks) and how effective they were in slowing the spread of this deadly disease.

Read the other posts on Historic Epidemics:

Parrot Fancier’s Fever: Part 1 — how my daughter and her quail keeping led to learning of a 1930s epidemic

Parrot Fancier’s Fever: Part 2 — how a 1930s epidemic led to the creation of the National Institute of Health

Historic Epidemics: Malaria in the Vatican 1623 — How the indigenous people of South American saved millions of lives

To get all my posts in your email subscribe here: