The Hebgen Lake Earthquake of 1959 struck on a moonlit August night in western Montana,…

Historic Epidemics: The Face-Mask Mandates of 1918

Are masks the answer to getting back to a ‘new normal’ after COVID19?

During the 1918 influenza, the widespread use of masks was a source of both confusion and controversy. Some cities and states implemented wide-spread mask usage. Others scoffed at the effectiveness.In the fall of 1918, as the second and most lethal wave of the ‘Spanish Flu’ spread through the United States and the world, cities debated their individual responses. Some closed public places and cancelled events while hospitals scrambled to treat the thousands of sick. Other cities went on as if all was normal, with lethal results.

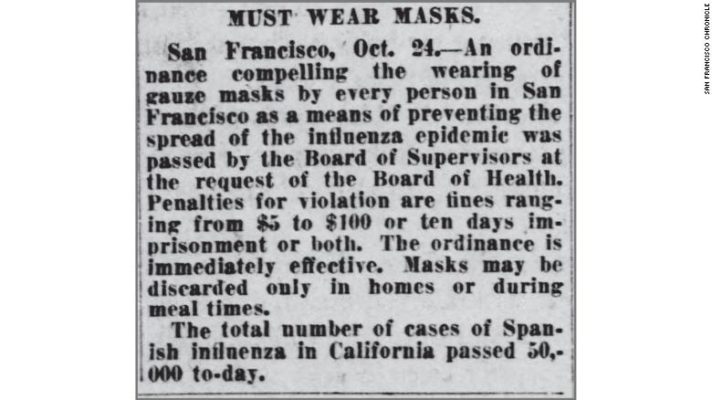

With more than 50,000 reported cases of the “Spanish Flu” in California in October of 1918, the board of directors of San Francisco passed the Influenza Mask Ordinance which made wearing face masks in public mandatory. San Francisco citizens found outside without a mask were fined $5 (quite a sum in those days) and charged with disturbing the peace.

Other California cities, including Los Angeles and Santa Cruz, instituted the same kinds of laws, followed by some states. The policies varied from ‘recommended’ to ‘required’. The police chief of Tuscan Arizona encouraged mask usage by stating that no public gathering would be considered ‘fashionable’ unless the attendees attire included face masks.

Campaigns for mask usage sprang up around the country led by local boards of health and the Red Cross. The public information campaigns even included some catchy slogans:

“Wear a Mask and Save Your Life!”

“Obey the laws, and wear the gauze. Protect your jaws from septic paws.”

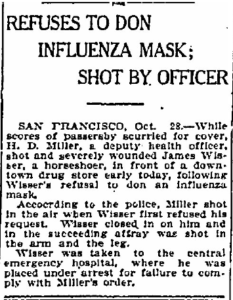

In Bellingham, WA, a healthcare officer shot and severely wounded a horseshoer who refused to wear an influenza mask.

Then, as now, widespread mask usage led to shortages, especially since there were even fewer manufacturers of medical grade masks worldwide than there are now. This, again as now, led to the home production of face masks. Communities came together collecting stashes of gauze and holding mask-making sessions in churches and homes (which probably wasn’t a good idea).

There were instructions on how to make the ‘flu fences’ or ‘chin sails’ in newspapers around the country. A piece of gauze the size of a ‘typewriter paper’, folded twice, with strings attached at each of the four corners to tie around the head. People were advised to wear them tightly tied and not to touch them after they were put on. The masks were to be boiled for five minutes after each use.

Others weren’t convinced of the usefulness of the face mask. Some physicians likened the four-layered gauze masks to attempting to keep out dust with chicken wire. In other words, useless.

So was the widespread use of masks effective in reducing the spread of influenza?

Not really. And maybe.

Because the masks, especially the homemade variety, were made of inferior materials for stopping the spread of a microscopic virus, they probably weren’t as effective as they could have been. But even a reduced effectiveness was likely some help in slowing the transmission of the virus. Masks were also likely a visual reminder in public that increased social distancing (before social distancing was even a thing). At the very least, they prevented public spitting which was a pretty common (and disgusting) habit.

That being said, here’s an interesting anecdotal account of how masks may have helped in at least one instance:

During the height of the pandemic, an ocean liner arriving in England reported a terrible influenza infection rate on it’s journey from New York. The captain, who had heard of San Francisco’s mandate, ordered all crew and passengers to wear face masks for the return journey. When the ship docked back in New York, no infections were reported present among any crew or passengers, despite high infection rates in Southhampton when they had departed.

So, the widespread use of masks may have been nominally helpful in slowing the spread of the 1918 Influenza, but in the end this virus devastated the worldwide population, killing 50 t0 100 million people — 675,ooo in the United States. By the summer of 1919, the epidemic subsided as those who had it either died or developed immunity.

Read my the other posts on Historic Epidemics:

Parrot Fancier’s Fever: Part 1 — how my daughter and her quail keeping led to learning of a 1930s epidemic

Parrot Fancier’s Fever: Part 2 — how a 1930s epidemic led to the creation of the National Institute of Health

Historic Epidemics: Malaria in the Vatican 1623 — How the indigenous people of South American saved millions of lives

Speaking of masks, for my next post I’m going to move on to something super interesting (to me at least) the plague masks of the Black Death or the Bubonic Plague. Did they really look like this and why were they so creepy? To get my posts in your email, subscribe up on top right of this post.