The Hebgen Lake Earthquake of 1959 struck on a moonlit August night in western Montana,…

Historic Epidemics: the Dancing Plague of 1518

As my last post on the Historic Epidemic series, this one is a little less serious. And yes, the Dancing Plague of 1518 was a real thing—no matter how ridiculous it sounds.

This mysterious plague wasn’t a one-time occurrence in 1518 but something that historians find reference to over the course of hundreds of years, and in places all over medieval Europe.

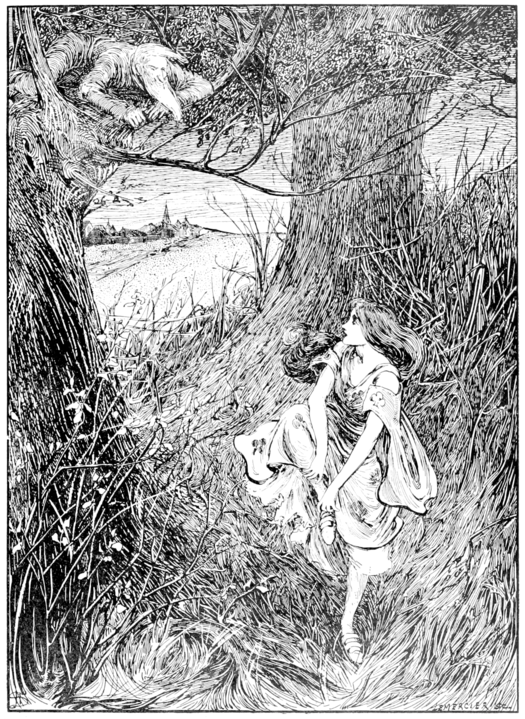

The best-documented of these plagues took place in 1518. Historical documents of the time all agree that in July of that year, in the streets of Strasburg, Alsace, (now France) a single woman began to dance in a frenzied way. More people, mostly young women, joined in. They danced in such a way–like they had no control over their actions–and for such a long time that the magistrates and finally doctors intervened, stopping them and confining the afflicted in a hospital. Accounts begin to differ after that. The number of dancers was reported as somewhere between 50 and 400. More than one chronicle of the event states that as men, women, and children joined in the dancing in the summer heat, fifteen people per day died.

More evidence instances of the Dancing Plague, also known as St. Vitus’ dance, can be found in primary sources from all over the medieval world:

- in the 1020s, Bernburg, Germany on Christmas Eve, 18 peasants began singing and dancing around a church in a frenzied way

- 1237 in which a large group of children could not be stopped as they danced and leaped twelve miles from Erfurt, Germany, to Arnstadt

- in 1278 a group of 200 people danced on a bridge that collapsed under their weight, killing some. Survivors were restored to health at a chapel dedicated to St. Vitus

- Another outbreak was documented in 1428, when a monk reportedly danced himself to death in Switzerland and a group of women in Zurich were afflicted with dancing frenzy

- In Trier, an abbot writes of a group of dancers “hopped and leaped” for six months, some of them dying from their injuries to their “ribs and loins”

Erfurt to Arnstadt, Germany

While it is hard to believe, the one aspect of the Dancing Plague that scholars seem to mostly agree upon is that the feverish dancing was involuntary. Throughout the historic documents, dancers were described as

- writhing in pain

- screaming for help

- in a trancelike state, unconscious of swollen or lacerated feet or even injuries like broken ribs from their frenzied dance

- begging for a physician or priest to put them out of their misery

So what was the cause of this mysterious illness? Nobody knows, but there are a few theories.

- the incidences of Dancing Plague often coincided with particularly harsh times of economic distress and social change, leading some scholars to believe it was a stress-related response to hardship

- A popular theory is that the dancers were suffering from ergot poisoning. Ergot is a fungus that can grow on rye and other crops during wet weather. Eating the rye, even after baking, would result in hallucinations, convulsions, and often end in death. But ergo poisoning alone can’t explain some of the symptoms of the Dancing Plague.

- Mass hysteria could be the cause. Some of the popular beliefs of the time was that there were spirits or witches that could inflict a ‘dancing curse’ to punish anyone who displeased them. When one person began to dance, others who thought they were under a spell would join in and soon the mania would take over the town.

Whatever the cause–whether medical or psychological–there is more than enough historical evidence to conclude that the Dancing Plague was a real thing in some way. Unfortunately, we probably won’t ever know much more about it than we do right now.

I hope you’ve enjoyed these short articles about historic epidemics. If you’ve missed any, you can find them here:

Parrot Fancier’s Fever: Part 1 — how my daughter and her quail keeping led to learning of a 1930s epidemic

Parrot Fancier’s Fever: Part 2 — how a 1930s epidemic led to the creation of the National Institute of Health

Historic Epidemics: Malaria in the Vatican 1623 — How the indigenous people of South American saved millions of lives

Historic Epidemics: The Spanish Flu didn’t come from Spain — how politics and the media put the spin on Influenza

Historic Epidemics: The “New Normal” after the Black Death

My latest novel, tentatively titled In A Far Off Land, is on its way to publication. With that in mind, I’ll be starting on a new series of blog posts. I hope you’ll join me in discovering the glamour and intrigue 1930s Hollywood! Sign up for my newsletter to make sure you don’t miss any:

This Post Has One Comment

Comments are closed.

I have enjoyed this series and look forward to the next.